|

A Bond is a Bond is a

Bond

Thoughts on the 70th Anniversary Editions of the original James Bond

novels

by

John Cork

Years ago, Dr. Seuss Enterprises decided that six of the author’s

books should no longer be published. “These books portray people in ways

that are hurtful and wrong,” the organization said in a statement. This

was news to the millions who had read these books as kids and had never

seen any evidence that Dr. Seuss had ever portrayed anything in a

hurtful way. “Ceasing sales of these books is only part of our commitment

and our broader plan,” the statement said.

For me and millions of others, a chill ran down our spines. Nothing good

can come from a sentence that begins “Ceasing the sales of these books…”

Now comes word that the James Bond novels are being altered to some degree

to adapt the language to more modern sensibilities. Is this censorship? Is

this another example of “woke culture” run amok? |

|

|

Too often in our modern

world we encounter those eager to tell us everything they see as wrong.

Sure, an objective reader would agree that attitudes expressed in the Bond

novels are often racist, sexist, and homophobic. Does that mean anyone who

enjoyed those novels must be polluted with those biases? I don’t think so.

For example, James Bond sleeps with a gun under his pillow in CASINO

ROYALE (1953). As an American who has read the novels numerous times, I

don’t own a gun. Nor do I own Bond’s attitudes, prejudices, or biases.

Heck, I can tell you how to make a Vesper martini, but personally, I don’t

drink.

When it comes to the Bond novels I try to hold to an old dictum: pick the

flowers, not the weeds.

I can love what I love, and set aside the rest as fascinating

archaeological evidence of the era in which Fleming wrote. Yet, as the

years slip past, the burden of being a fan of Fleming’s writing has grown.

What do we do with the passages that seemed so fresh and edgy in the 50s

and 60s, but now seem at best clunky and, for many, casually and cruelly

offensive?

The Bond novels could be allowed to slip out of print. Maybe Ian

Fleming Publications could issue a self-congratulatory statement along

the lines of Dr. Seuss Enterprises. Or they could pretend times

have not changed hoping that no ‘Twitter Social Justice Warrior’ decides

to start a campaign to cancel the works of Ian Fleming.

Or the Fleming family members who control the publishing rights could take

a more difficult path and try to gently adapt the books in some way to

make them accessible to modern readers.

Is this some level of absurd self-censorship? Is Ian Fleming spinning in

his grave?

I don’t think so, and I believe I have the receipts to prove my point.

|

|

|

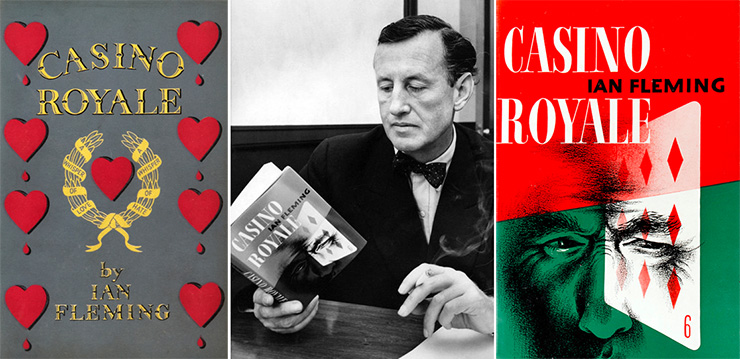

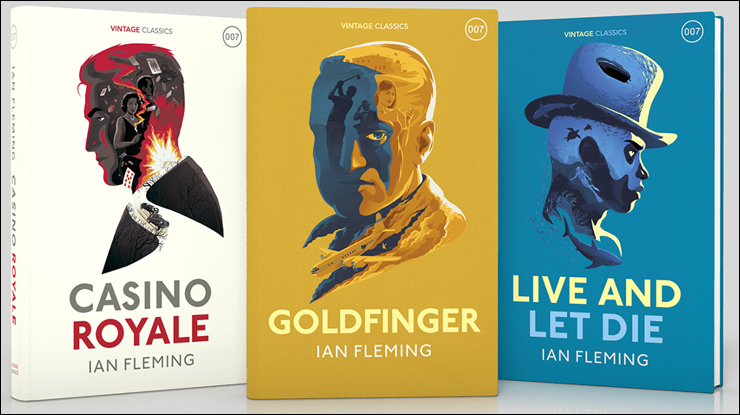

In 2017 I was asked to

write introductions to three Bond

novels for hardback editions published by Vintage Classics in

the UK; the titles CASINO ROYALE, LIVE AND LET DIE, and GOLDFINGER. I

immediately reached out to Penguin and Ian Fleming Publications

with a note on May 9, 2017, which included the following:

“I presume the plan is to use the British text from the first edition.

But I am ever hopeful that the American edit might be used. The reason I

bring this up is that when Al Hart edited the book for America, he worked

with Fleming to correct numerous factual errors and to work around some of

the more offensive passages.”

Ten days later, Ian Fleming Publications and Penguin agreed

that they should review every edit made for the US publication of LIVE

AND LET DIE in April 1955. Fortunately, Bond scholar Bryan Krofchok

compiled a meticulous list years earlier that was published in issue #4 of

Goldeneye Magazine, which I edited during its brief life in the

1990s. Krofchok’s work provided the basis for creating the edition

published by Vintage, which, aside from a few small passages that

were retained from the British edition, mirrors the US edition.

The statement from Ian Fleming Publications addressing the 2017

edition of LIVE AND LET DIE is correct: Ian Fleming approved every edit

that Al Hart made to that text.

There was no alternate US edition of GOLDFINGER, which contains passages

that are decidedly racist towards Koreans. “They are the cruelest, most

ruthless people in the world,” Auric Goldfinger exclaims.

Bond himself joins in later when Fleming writes, “Bond intended to stay

alive on his own terms. Those terms included putting Oddjob and any other

Korean firmly in his place, which, in Bond's estimation, was rather lower

than apes in the mammalian hierarchy.” |

|

|

ABOVE: (left)

American character actor Henry Silva (1926-2022) as Korean manservant Chunjin in The Manchurian Candidate (1962). (centre) John

Frankenheimer's masterful film adaptation of Richard Condon's classic

1959 political thriller was later paired on a double-bill

with the first James Bond film Dr. No (1962),

for a New York revival in early 1964. (right) Hawaiian-born American

1948 Olympic Silver medal-winning

weightlifter, professional wrestler, and film actor Harold Sakata

(1920-1982) as Korean manservant Oddjob in Goldfinger (1964). |

|

|

|

No editor objected to

this overt racism. In explanation (but not defense), Fleming wrote these

passages when there was still great resentment in the UK to the actions

against British soldiers by Korean guards working for the Japanese in

Prisoner Of War camps during the Second World War. In the US, reports of

the tortures inflicted by Koreans during the Korean War, and sights of

brutal inhumanity during that conflict were still fresh in the minds of

military veterans. The view of Koreans as animalistic and cruel was so

prominent at the time that, as I noted in my 2017 introduction, GOLDFINGER

was not the only novel released in 1959 with a villainous Korean

manservant: The Manchurian Candidate featured Chunjin, a

cold-hearted former US Army interpreter.

But who among average readers is going to have this context at their

fingertips?

I have no idea if these passages have been altered in the 70th Anniversary

editions, nor if there is anything addressing Bond’s screed about how

giving women the right to vote somehow led to sexual confusion and the

spread of homosexuality.

No reviews from 1959 that I’ve read of GOLDFINGER ever mentions these

passages. This means Fleming was successfully reflecting the biases and

blind spots of the world in which he lived. How successfully? Fleming’s

editor at Jonathan Cape was William Plomer, a good friend of Ian’s. Ian

dedicated the novel GOLDFINGER to Plomer. In the notes Plomer sent Ian on

GOLDFINGER, he made no mention of Bond’s rant about homosexuality. I feel

confident that had Plomer asked Fleming to tone the passage down or remove

it, Fleming would have. Plomer, after all, had brought Fleming’s original

typescript of CASINO ROYALE into Jonathan Cape, his recommendation

securing Fleming a publishing deal. Plomer had every motivation to look at

the passage with careful consideration because, of course, Plomer was gay.

Fleming had numerous gay friends: Noel Coward, W. Somerset Maugham are two

obvious examples. Yet, at the time, the literary convention concerning

homosexual characters involved a denouncement of just the sort that

Fleming included in GOLDFINGER.

Is it wrong now that there be a version of the novel published that

considers what Plomer might have said to Fleming had he not lived in an

era where homosexual behaviour was criminalized? An era where if Plomer

was arrested for homosexual activity he would face jail or chemical

castration? |

|

|

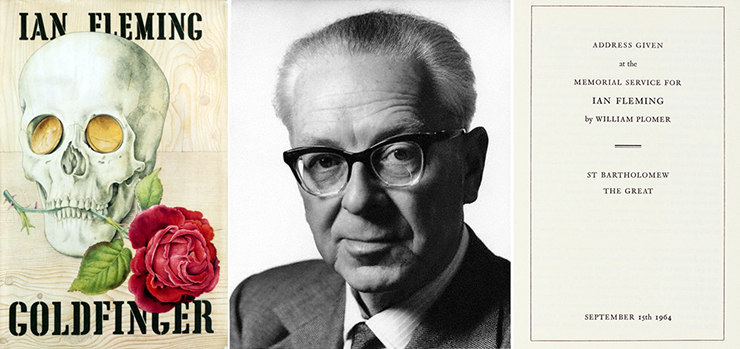

ABOVE: (left) The dust jacket for the Jonathan Cape

hardback edition of GOLDFINGER (1959) illustrated by Richard

Chopping (1917-2008). (centre) GOLDFINGER was dedicated to Ian

Fleming's friend the South African born novelist, poet and

literary editor William Plomer (1903-1973), who would later write

the address for Ian Fleming's memorial service (right) held at St.

Bartholomew The Great in London on September 15, 1964.

|

|

|

|

Maybe one believes

the thoughts Fleming attributed to James Bond are so integral to the

core of the novel that altering them would destroy any integrity in

Fleming’s writing. Fleming certainly didn’t see things that way.

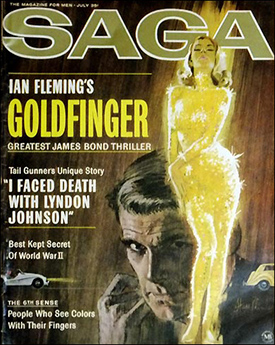

For example, when the novel GOLDFINGER was published in the July 1964

issue of SAGA magazine, Ian Fleming was still alive. And, yes,

Auric Goldfinger’s assessment of Koreans is still in the text. Bond’s

offensive views are not. And Bond’s mental rant about “pansies of both

sexes being everywhere” is nowhere to be found.

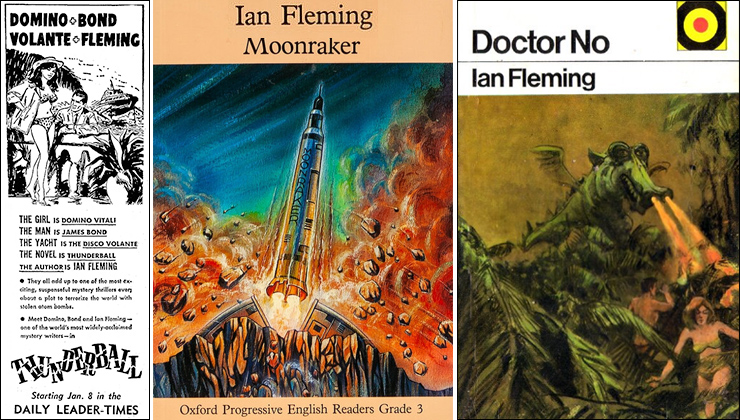

Heavy edits were made to the Daily Express serializations of

the Bond novels during Fleming’s lifetime, as well as to the US

King Features Syndicate 1962 serialization of THUNDERBALL in

newspapers (see Daily Leader ad below).

PLAYBOY made major

edits to the Bond novels they published during Fleming’s lifetime.

Fleming himself had to approve each one of these publications of his

work. This means he either read the edits and approved, or he simply

trusted the editors to make wise choices for their markets.

It is hard for me to believe that Ian Fleming would not tacitly

approve of the concept of updating some language and omitting certain

portions of the novels, since he participated in this during his

lifetime.

These editions are not even close to the first time the novels have

been altered since Fleming’s passing. |

|

If you want to read some

seriously sanitized versions of the Bond novels, seek out the ‘adapted’

editions for early readers. Oxford University Press published two

separate editions of MOONRAKER, one for adults learning to read English,

and another for younger readers. There are

Bulls-eye

young reader editions of many of the titles from the mid-1970s adapted

by Patrick Nobes. |

|

|

One can also find old,

abridged audiobook editions of the Bond novels, all released without fuss.

When I think of all the different editions and lives of the Bond novels, I

think also about a novel Ian Fleming quite loved: All Night At Mr.

Stanyhurst’s, first published in 1933. In 1963, Fleming’s publisher,

Jonathan Cape, reprinted the novel with a new introduction by James Bond’s

creator. The book still did not catch on. For the past 60 years, it has,

to my knowledge not been reprinted. “How often are books raised from the

dead…?” Fleming quotes from a Times Literary Supplement article in

his introduction. Not often, is the brutal answer. Most novels disappear

without a ripple. Some books, like the six Dr. Seuss titles

retired, are memory-holed on purpose. Others seem to become strange relics

of the past.

Then there are the James Bond novels, which barely seemed dated when I

first read them in the mid-1970s, and now seem like fascinating (and

exciting) cultural artifacts of the Cold War. Will these novels survive?

Only if we let them. Only if we are not so precious about them in ways Ian

Fleming never was. Would it be wrong to re-publish the SAGA magazine

version of GOLDFINGER? It was the last re-edit of the novel published in

Fleming’s lifetime.

The Holy Bible appears in not only The King James edition,

but the New American Standard, the Revised English Bible,

the New English Bible, the New International Version, the

New Standard Version, the New Living Translation, the

Tyndale Bible, the Revised English Bible, and the New King

James Version – to name a few. Each edition alters the language, and

for some, the meaning. Older editions that referred to “men” and “man”

have been replaced by newer translations that use language that includes

women. “No one can serve two masters” replaces the King James “No

man can serve two masters,” for example. I don’t think these revisions

were undertaken to accommodate snowflakes. |

|

The Bond novels

continue to exist in their original form. There are hundreds of

thousands of English-language copies of each of the Ian Fleming Bond

titles available, versions that reflect both the original UK text and

the versions separately edited for the US printings. Those editions

are not going anywhere, and if there is strong demand for the original

text, Ian Fleming Publications would almost certainly print new

versions that adhere to it.

Are these edits a good idea? Will the public embrace them? Would

anyone have noticed if not for the current fascination with culture

wars? This type of revision happened many years ago with Hugh

Lofting’s Doctor Doolittle books. No one seemed to care. Roald

Dahl revised Charlie and the Chocolate Factory after some

pointed out the offensive descriptions of the Oompa Loompas.

For me, these are just another edition of the Bond novels, another

chapter in the strange and captivating history of the 007 literary

phenomenon. I’m interested in reading the minor textural changes,

seeing what the editors chose to revise.

|

|

|

John Cork is the co-author of three official books on the Bond phenomenon,

a writer, producer, and director for many of the special features found on

the James Bond Home Entertainment releases through 2006’s Casino Royale.

Cork is currently developing a podcast looking at how the original James

Bond novels interact with history. |