|

EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW |

||

|

||

|

EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW |

||

|

||

|

|||

|

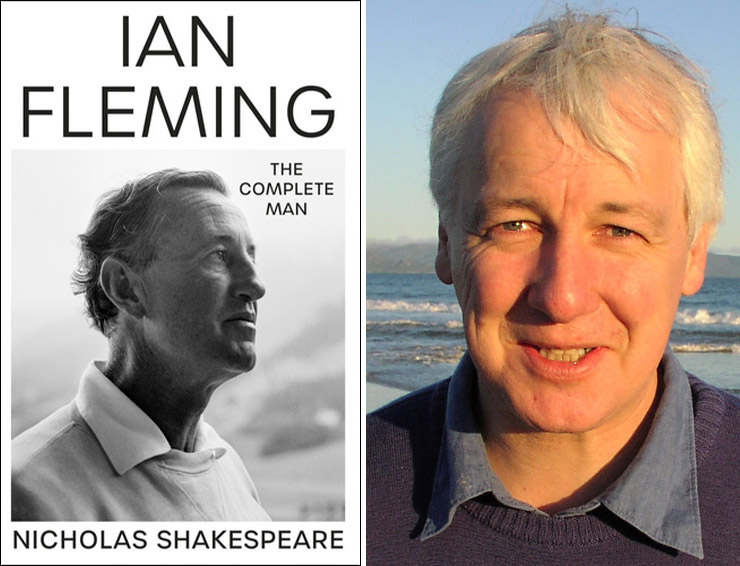

Nicholas Shakespeare is Ian Fleming’s latest – and arguably definitive – biographer. His recently published masterpiece Ian Fleming: The Complete Man, skilfully draws on previous biographies – principally those by John Pearson (1966) and Andrew Lycett (1995) – while also offering a plethora of fresh ideas, insights, and information. If you’re an Ian Fleming fan or admirer, it’s quite simply a must-have item for your Bondian bookshelf. Earlier in 2024, Shakespeare kindly agreed to be interviewed by 007 MAGAZINE chief writer LUKE G. WILLIAMS, and the results of their in-depth discussion are published here for the first time. |

|||

|

|||

|

When did you first encounter the work of Ian Fleming? What were your views

on him before you wrote this book? And what factors were at play when you

came to decide whether to accept the offer to write the book or not? About Fleming himself, I knew little. What I gathered from sideways glimpses was not especially savoury. It dawned on me only very recently that a moral of his story is this: don’t run off with the wife of the owner of the Daily Mail if you wish to avoid forever after being rendered into tabloid fat. The cartoonish impression I formed was of an Old Etonian bounder, a desk-bound ‘Chocolate Sailor’ in the war, who after WW2 spends his life hitting the road after whipping his wife, returning home in the early hours, following an evening of bridge-playing at his club, or a day on the links at the Royal St George’s golf course, fortified on an undeviating diet of scrambled eggs, Martinis, and Turkish cigarettes. Not very appealing. That’s why, when first approached by the Fleming Estate in 2019 to write a new authorised biography, the first since 1966, my initial reaction was hesitation. Did I wish to spend the next four or five years in the company of a melancholic cad and creator of the cold killing machine, James Bond? This incomplete image was my only image of Fleming. |

|||

|

|||

|

Before rejecting the proposal, I did some background research. What clinched my decision was my stumbling on mysterious connections which suggested that Fleming might be a propitious subject after all. By a strange set of coincidences, before he joined Fleming as his ‘leg man’ on Atticus, John Pearson, Fleming’s first authorised biographer, had shared a desk at the Times Educational Supplement with my father, who himself went on afterwards to perform an identical role for Fleming’s successor as Foreign Manager, Frank Giles. After I brought the two former colleagues together for lunch 66 years later, Pearson gave me his blessing to enter his biographical domain and handed me a gift: his ‘Fleming file’. There were more Shakespeare links. In 1915, my paternal grandfather and Fleming’s father Val Fleming had breathed in the same cloud of chlorine gas at Ypres when Val helped Major W. G. Shakespeare carry 359 stretchers to a field. For the first months of WWII, my great-uncle Geoffrey Shakespeare worked directly above Fleming’s desk in Room 39 when Geoffrey was Churchill’s “indefatigable second in command” at the Admiralty. From a younger generation, my eldest son was in the same house at [Eton] school as Ian Fleming, and was Victor Ludorum like him. I found connections on my mother’s side too. Her father, the prolific author S. P. B. Mais, who had taught Alec Waugh at Sherborne and got published his first novel, The Loom of Youth, had impressed on Waugh the inflexible rule for his writing: 2000 words a day without fail, sticking to a routine “from which nothing must be allowed to deter you”. Waugh would pass on this vital advice to Fleming, along with Mais’s story about our Jamaican relatives that had inspired, so Waugh’s son Peter believed, Alec’s 1955 bestseller Island in the Sun – the Hollywood film of which impressed a young music producer in Jamaica to name his company Island Records: Chris Blackwell is now the owner of ‘Goldeneye’, where Fleming wrote all 14 Bond books. On my wife’s side, a coincidence spookier still. It was her Icelandic-Canadian father, Dr. George Johnson, who is credited with revealing the true identity of William Stephenson, ‘the Quiet Canadian’ and ‘Man called Intrepid’, whom Fleming once saluted as his chief model for Bond. In 1980, Dr. Johnson disclosed why Stephenson had not dared step foot in his Winnipeg birthplace since 1922. In that year, the quiet Canadian had fled Winnipeg as a bankrupt, having swindled 95 investors, many related to my father-in-law’s patients, following the collapse of a company fabricating can-openers. Further, Stephenson had not been called Intrepid, this was the cable address for his wartime office in New York. He was not even called Stephenson, but Stanger, the son of an Icelandic mother who had abandoned him to my wife’s relatives, the Stefánssons, whose anglicized surname he adopted. Excited to discover these tenuous links, I said yes [to writing the book]. |

|||

|

|||

|

What was the most interesting or unexpected thing you discovered about Ian

Fleming in the course of your research? Kinder, but also a great deal more significant than his popular caricature, his many jealous critics had inferred that in WW2 [Fleming] was merely in charge of ‘in-trays, out-trays and ashtrays’ at the Admiralty, where he served as PA to the Director of Naval Intelligence, Admiral John Godfrey. In fact, Fleming was in the inner citadel of British Intelligence, one of only 30 people cleared to know the top wartime secrets of Bletchley Park, and one of only a handful of trusted insiders who helped set up America's first foreign intelligence organisation, the COI, with Colonel William Donovan, in the spring and summer of 1941; in 1947, this became the CIA. When Churchill (who wrote the obituary of Fleming's father, killed at the front in 1917 when Fleming was 8) talked in 1946 about a “special relationship”, he was talking about what was first and foremost an intelligence relationship. Few had done more to make it so special than Ian Fleming, who was regarded by Admiral Godfrey as a “war-winner”. Oh and Fleming wasn't just responsible for Bond: he also came up with the idea for The Man From U.N.C.L.E. (he later sold the idea to MGM for £1) and for the character of Charlie in Charlie's Angels. After five years in his company, I came to agree with his friend Robert Harling, who described Ian Fleming as “the most generous, least malicious, most merry yet most melancholy man I ever knew”. |

|||

|

|||

|

Can you describe some of the previously unseen sources and information you

were able to access for this book? How supportive were the Fleming family

of your editorial freedom? |

|||

|

|||

|

You’re a biographer but also a novelist. How would you define your

approach to biography and to what extent do you incorporate novelistic

techniques within your biographical writing? I’m also interested in the

book’s approach to chronology. Broadly it’s structured chronologically but

there are also sections which are more thematic where the broad chronology

is disrupted… |

|||

|

|||

|

As with my previous history, about Churchill unexpectedly becoming Prime Minister, Six Minutes In May, I drew on fiction-writing not to invent a single thing, but to help sift and structure the material; to keep the reader engaged, on their toes, suspended – as well as to pry with unusual nosiness into character and motive. The structure of Ian Fleming: The Complete Man largely presented itself – save for the opening, which took many rewrites. I knew immediately that I wanted to begin with Fleming’s funeral in 1964, how it had to recommence all over again – this seemed a perfect illustration of what I was trying to persuade the reader to do, i.e. re-examine Fleming, a person we all think we know perhaps rather too well, from the start. I also experimented with the 1960 Kennedy dinner party in Washington as a possible opening. But that presented rather too many beginnings, so I returned the dinner to its correct sequence in the narrative. The only other subversion of order was the chapter when the Old Harrovian ornithologist James Bond visits ‘Goldeneye’ in February 1964, near the end of Fleming’s life. I felt that this encounter wouldn’t work in strict chronological order, when it would risk reheating a lot of old cabbage; but to put it directly after Fleming writes CASINO ROYALE might inject his own story with a fresh and unexpected fillip. Plus, it allowed me to give an overview of the remaining body of work: the idea first brilliantly mooted by Philip Larkin that each Bond novel was a piece of stolen bullion from WW2. One other influence (of my suppressed novelist’s instinct) can be detected in the story of Evelyn Waugh performing the word “bondsman” at a family charade shortly after Fleming’s funeral. I was told this years ago by the Waugh family when I made a three-part documentary on Evelyn Waugh for ‘Arena’. It seemed a perfect encapsulation of Fleming’s sad, Frankenstein-like life story, and I was determined to include it somewhere, the devil was where. It appeared in various parts of the book until it settled in its present position. The incident which forms the book’s ending is quite shocking and

devastating. At what stage did you decide that this would be how you would

end the book? |

|||

|

|||

|

Any tantalising details of things you had to leave out? |

|||

|

|||

|

©007 MAGAZINE April 29, 2024 |